Babies Spot Languages Just by Watching

Mouth shapes are enough to distinguish one language from another. Even before they begin to speak themselves, a young baby can tell when you're speaking a different language just by looking at your face. Canadian researchers came to these conclusions after studying videos of babies from monolingual and bilingual homes. But unless they are growing up in a bilingual home, babies lose this skill by the time they are eight months old.

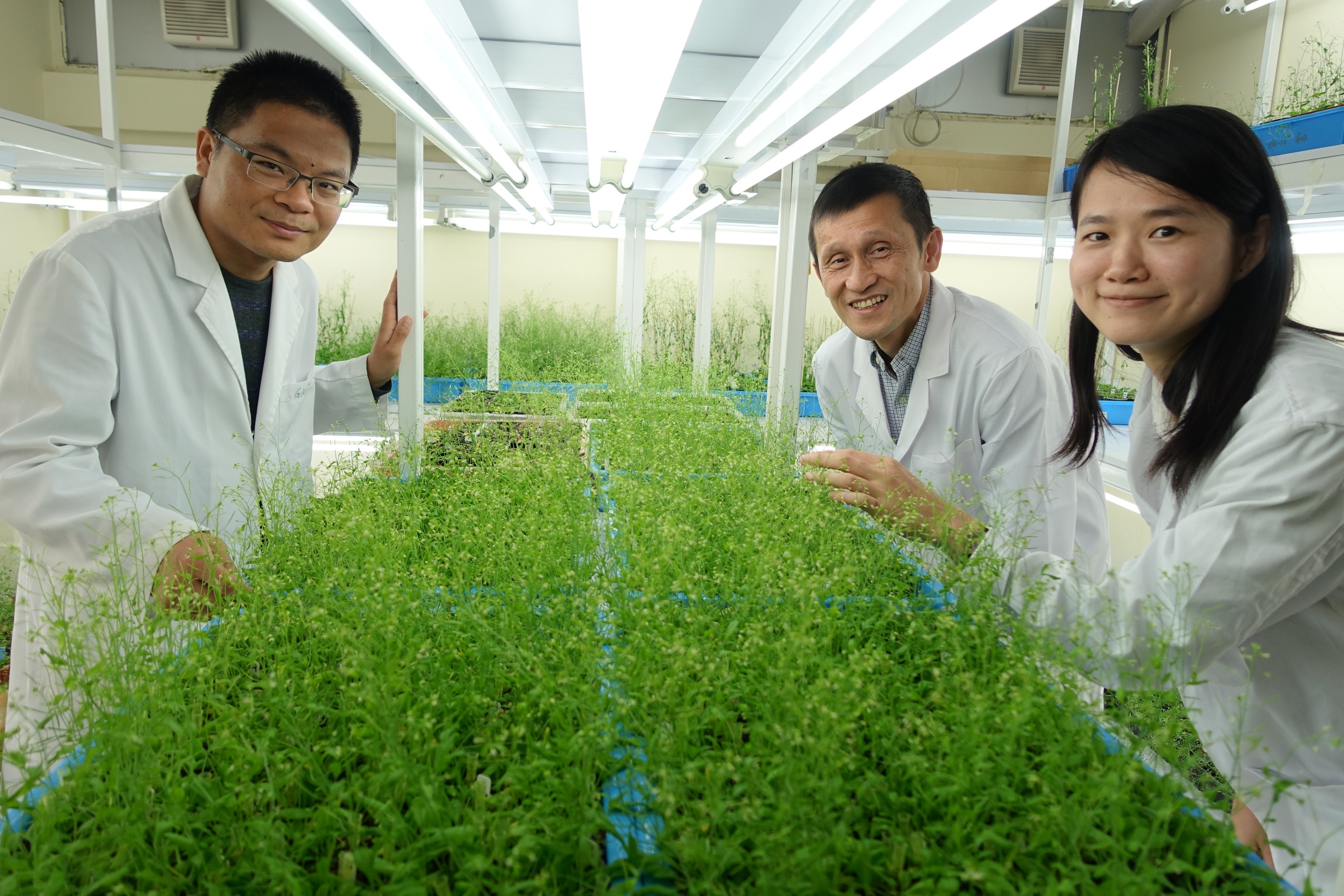

The study shows the importance of visual cues, such as the shape of the mouth, for babies in the early stages of acquiring language. Babies are good at linking certain bits of information about speech — such as the shape of the mouth and the sound that accompanies it — and can distinguish between mouths making 'ooh' and 'ee' sounds, for example. But this is the first time it's been shown that they can distinguish different languages from visual cues alone. But this ability soon disappears, however, if babies are exposed to only one language home. This came as a surprise to the researchers. "I really expected this ability to progressively get better over the first year of life," says Whitney Weikum of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, who led the study. The group tested a total of 36 babies aged four, six or eight months from English-speaking homes, and aged six and eight months from French-English bilingual families. The infants watched silent video clips of bilingual speakers who recited sentences in either French or English, and then switched to the other language. All babies from bilingual backgrounds looked for longer at the videos in which the language being spoken was switched than at those in which no switch was made, showing that they noticed the change, Weikum and her colleagues report. At four and six months, the babies from exclusively English-speaking families behaved in the same way, continuing to stare at videos in which a switch was made. But by eight months old, the English-only babies no longer noticed a change, the researchers add. Their results are reported in Science (1).

Use it or lose it "I'm surprised that infants would lose that ability," says Kim Plunkett, a neuroscientist at the University of Oxford, UK, who studies language learning in infants. Mouth shape is a very prominent feature for a baby, he explains. "If the shape of the mouth started doing something weird, I'm surprised the baby wouldn't notice." One reason for this decline in ability, suggests Weikum, is that telling languages apart visually isn't something that monolingual babies need to be able to do. What's more, the decline fits a pattern: babies also begin to lose other skills at around the same age. For example, they can no longer discriminate sounds or rhythms from other languages that are not present in their own. But the extent of the loss is not known. "We really don't know if this drop-off is just a decline or a complete loss," says Weikum. The team next plan to find out more about what cues in the speakers' faces the babies are using to help them spot the difference. Written By Kerri Smith Retrieved From: http://www.nature.com/news/2007/070521/full/news070521-11.html References Weikum W., et al. Science, 316 . 1159 (2007).

|

|