A Woman’s Breasts Can REMEMBER Being Pregnant

It has long been recognised that for those mothers able to breastfeed their babies, second time around is not as difficult as the first time. Now, US researchers have discovered why.

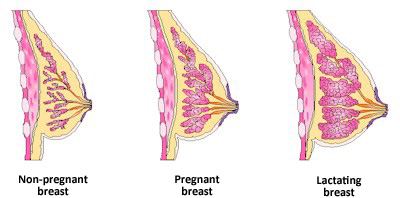

The mammary gland, the part of the breast that produces milk, has a 'memory' of being pregnant, they found. This means the next time a woman is expecting, her body quickly responds to the changes in hormones to produce milk more quickly. Moreover, the researchers found this memory may last throughout a woman's reproductive lifetime. During pregnancy, the release of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone trigger changes in the breast that prompts milk to be produced. The breast cells divide, and thousands of ducts form, which transport the milk during lactation. The researchers hypothesised that being pregnant might alter the mammary gland's receptiveness to oestrogen and progesterone. They wanted to know if this change might occur due to changes in chemical 'marks' that attach to DNA. These marks – which are usually molecules of methyl (CH3) - are called epigenetic marks. Whether or not they are present in DNA can either prevent certain genes from being expressed, or promote their expression. Using stem cells from mouse mammary glands, they found that the cells from mice who had previously been pregnant had marks that were 'substantially different' from the cells of mice of the same age that had never been pregnant.

The team also found that that becoming pregnant also erased many marks that are present throughout life leading up to pregnancy. The marks bound to DNA in mammary epithelial cells at places near genes that need to be activated during pregnancy - specifically, genes involved in making the breast cells divide, and lactation. When they gave the mice who had previously been pregnant hormones which simulate a real pregnancy, they responded more rapidly than other, never-pregnant mice given the same hormones. In the previously pregnant mice, 'the mammary glands start expanding faster and also sooner than for those experiencing pregnancy hormones for the first time,' researchers said. Camila dos Santos, an assistant professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), said: 'It's as if the gland already knows those hormones.' When they analysed the same parts of the cells a year after 'pregnancy' (or exposure to pregnancy hormones), the cells remained free of marks. Dr dos Santos, added: 'This means the memory of previous pregnancy is long-term.' These findings have led to another important line of research. It is well known that women who become pregnant by the age of 25 have substantially lower rates of breast cancer than women who bear children later in life or not at all. It is possible the protection against cancer might be linked to the 'memory' of mammary cells the scientists discovered, they said. Dr. dos Santos said she and her team are now trying to understand which changes to breast cells during pregnancy might prevent the development of breast cancer. The results were published online in the journal Cell Reports.

Written By Madlen Davies Retrieved from:

|

|